This post is my reflection and notes on the book “The Future is Bi-vocational” by Andrew Hamilton (Hamo), a Perth pastor and small business owner / reticulation guy arguing that churches should start shifting away from assuming “full time pastors” is the right way to lead a church community, and arguing that people who can lead churches might have a lot to benefit from having a different non-church job as well. It’s an easy read, well written, full of stories from his decades of experience. The target audience seems to be existing full-time pastors, or students studying to work in church, but if like me you already have a different career but sense a pull to contribute to your church community in a way that’s slightly more than just volunteering… it’s still a great read – convincing and inspiring. Available on Amazon, or probably local Christian bookstores if you’re in Australia.

Before I share my notes and takeaways, here’s a reflection on where I’m at, and what I had in mind as I started reading.

I was only five or six years old the first time I had a sense that when I was a grown up I’d likely do pastoral work, serving and leading a church community.

That sense stayed with me all through school, and into university. Though I chose to study Multimedia Design rather than go to a bible college or seminary, I still kind of assumed that ultimately it was just filling in time until some kind of a church role. By the time I was in uni I was volunteering a lot, leading groups the size of a small church, sometimes even preaching. And when I was doing those things there was a grace to it: things flowed, there was wind in the sails, there was energy in the room.

Of course part of it was some natural talent, some hard work, some early-adulthood energy. But there was also something more than that, beyond what you would expect from natural talent or effort… something undeserved. A grace.

I was so sure I’d end up working in church that I almost turned down my first software engineering job. I’m glad I didn’t.

I was newly married and Anna was sick, I’d become the sole income earner, and I didn’t want to take the job because I thought I was likely to get one at church within a few months. But I felt a sense that God was saying to me: “this is me taking care of you”. So I took the job. Software jobs pay a lot better than church jobs, which helped. A few months later the church had layoffs… it turns out I wouldn’t have gotten that role anyway.

Over in the software industry I found there was a grace that followed me around there too. Yes I had skills, yes I worked hard, but there were also opportunities I wouldn’t and couldn’t have orchestrated. Whether it’s cultural privilege or being blessed or something else, I’m not sure, but it was beyond what I felt I deserved. Again – grace.

And then, 15-ish years into this career, some thoughts start bubbling up, something is stirring, and I start thinking about the church stuff again. About using my skills, and finding that grace, in a church context. Don’t get me wrong, I love my work and career, and don’t plan on leaving… but there’s an internal pull to explore the grace of serving a church community, again.

Both to traditional church – using my skills in leading groups and public speaking to help people connect with each other and with God. But also in less traditional forms of community – facilitating community meetups, speaking at tech conferences. Being friends with people in the community so you’re available to help them find their way in key life moments – births, deaths, sickness and hospital stays, marriages and breakups. Helping kids and teenagers feel a sense of community they can belong to beyond their family and school friends.

It’s all stirring together into something. In amongst still enjoying my career and intending to continue it.

So when my mum mentioned her friend was writing a book called “The Future is Bi-vocational”, my interest was piqued.

Now that I’ve shared part of the story of my vocations – I’ll share what I learned from Andrew Hamilton’s book.

The future is bi-vocational

In the opening chapter Hamo remembers a conversation when he was about to start a new church, and he was given advice that “a viable church had 100 members and that I needed to grow my congregation to that point as soon as possible”. And so begins the unwinding of a bunch of assumptions about how to run a church: do you need to pay the salary of someone full time for the community to be viable?

For most of Christianity’s 2000 year history, we’ve had full time pastors who hold a privileged position in the community. But as society becomes both more secular, and also more religiously diverse at the same time, the assumption that a pastor can work in a church building, and the community will come to them, is not holding up anymore. That’s the mission problem we’re facing – it’s hard to care for a community if you’re in a building and the community doesn’t come to your building anymore. Also our suburban western culture often is suspicious of interactions with strangers, and so just leaving the building and starting up a conversation without a shared reason is also not an effective way to build relationships.

Then there’s the financial problem – as market pressures squeeze small churches in the same way big supermarkets squeeze small corner-stores, we’ll see increasing trends of there not being enough people in the small local churches to sustain a full time role through members giving part of their pay-cheque to the church. Bigger churches get better “economies of scale” for the surface level things people consider when church shopping: the quality of the Sunday preaching, music, and kids programs. A megachurch might be more financially efficient and effective in putting on a good Sunday service, but putting on a good Sunday service was never what church was supposed to be about. So the big churches start to attract people because of their more efficient and higher quality Sunday services, but then they need to spend their staff time on those services. The small churches can’t afford a full time pastor anymore, especially as they keep seeing their people switch to the bigger churches with the better weekend programs.

This feels like an existential problem for Christian churches… but in it Hamo sees a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. Once in a lifetime is probably actually too common: it feels like this might be one of the ~500 year moments in church history that Phyllis Tickle talks about. The shift is coming, the cultural forces behind are probably unstoppable, and what church looks like on the other side won’t be what it looks like now. And therein lies the opportunity which he makes the case for.

He’d started his career assuming if a pastor needed two jobs, it was a sad interim state to pay the bills. But his experience has been that the setup is rewarding for a variety of reasons, and in this he sees the opportunity for the church to transform itself and be more true to its values, more effective in serving the community, and closer to the vision of a “priesthood of all believers” that Jesus intended for us.

Here’s my notes on some of the things that stood out to me in the book.

No spectators

Remember the board game Pictionary, where people played in pairs, with one person sketching and another trying to guess what they were drawing, while everyone else watched? Often church is a bit like this. However, it ought to be more like the “all play” moments in Pictionary, where everyone is involved in drawing and guessing and no one is spectating.

One of the significant benefits that can come from a shift into the bi-vocational mode is that a sometimes-dormant church, with minimal congregational engagement, is challenged to step up and function as a cohesive unit. The body metaphor Paul uses in 1 Corinthians to describe the church community means simply ‘attending’ a church should never be an option. Everyone has a role to play, and a job to do, in order to keep the body healthy. Anyone can ‘turn up’. It’s another thing altogether to discover your own unique gifts, and then to serve alongside the others in your community.

I loved this line of thinking. In the same chapter he proposes a hypothetical situation: what if a church got up on Sunday and announced that all the paid staff halved their hours, and would be taking other jobs. How would the wider community respond? Would it do less? Is there work or programs that staff are keeping alive that aren’t really worth it? Or would the rest of the community pitch in and do more? Spreading the load among a wider group, and including a more diverse range of skills, gifts and experience.

Take this example: a church pays someone to coordinate crisis care for homeless and vulnerable people. Does the existence of this role mean people in the community think “that is someone’s job, I can leave it to them?” What happens if that job disappears, or is halved? Does the community step in and fill the gap?

Views of work

I love the way Hamo unpacked some of the prevailing views of work in the church:

- Work as cursed: we only work because this is a broken world. We didn’t work in the Garden of Eden, we won’t work in Heaven… we have to do it now, but that’s a shame.From a bible perspective, humans were working even back in the paradise of the Garden of Eden – work was part of the perfect plan, not part of the fallen broken version of reality. Work often is broken and feels cursed now, but fundamentally it’s supposed to be a good, creative, and meaningful pursuit.

- Work as income: we only work because we need the money. You also see this in technology-optimist or anti-capitalist thinking: if we just had enough technological automation or free clean energy, we could eliminate all toil. If we just had strong welfare, or universal basic income, we wouldn’t need to work. Another take is that work is about wealth accumulation, the harder you work the more money you get, and more is good.He reminds us that the Christian view is clear that a good day of work deserves good pay, but it’s also clear that toiling your life to earn wealth isn’t worth it. Yes we work to earn money, but making it just about the money strips us of the bigger meaning, and the dignity, in the value we provide.

- Work as service: Reminding ourselves that it’s not just about doing the tasks or getting the pay check, but the work we do provides value for someone, and doing it in a way that shows that person honour and respect and love, doing our work to serve them (and of course, still get paid), is a higher view of work.

- Work as worship: There’s a Christian work ethic spelled out by Paul in his letter to Colossians: work hard, as if you’re working for God and not just your boss. Hamo pointed out that the link between work and worship actually goes deeper, with a single Hebrew word being used in each of these places:

- Six days you shall labor, but on the seventh day you shall rest (Exodus 34)

- Let me people go, so they may worship me (Exodus 8)

- But as for me and my household, we will serve the Lord. (Joshua 24)

Advantages of bi-vocational model

Often Christian ministers call the idea of a second job “tentmaking”, a reference to the second job held by the apostle Paul, who was the most prolific writer in the Christian scriptures. His other job, which helped pay the bills, was making tents. In the chapter “Tentmaking – it’s not about the tents”, Hamo fleshes out some of the reasons why having a role outside the church is actually beneficial even for the work you do in the church context:

- Credibility: demonstrating you’re a hard working person with decent values, and you’re not just here to ask for money or to enjoy the status that comes with a leadership role.

- Positioning: you’re more likely to interact day-to-day with the kind of people that you’re hoping to serve. If you work in a church your connection with the wider community can be pretty limited because you don’t have natural places to interact with the community around you.

- Visibility: people will see how you work, and how your values hold up “in the real world”. It’s a chance to demonstrate the different values we preach about, in a visible way so people know it’s real for you.

- Freedom: as a church leader sometimes you need to challenge the community, rather than give them what they want. If you’re relying on them for donations, then you might be afraid to say the hard truths. You see a similar dynamic with politicians and their donors.

- Funding: relying on people giving from their income is always going to be limited. If you can sustain an income in a different way, it gives you more options for how you can do the church-based work without being limited by the bank balance.

- Flexibility: some roles allow you to move more freely. Either because the skills are in demand in different areas, or because they open the door for visas and migration, or because they allow “work from anywhere”. Some roles also allow flexibility in hours, either at a week-to-week or a seasonal level, which might match the flexibility you need for your work in the church community.

- Example: you want the whole church community to treat their work as worship, and a chance to bless the people around them. You can set the example. No one can say “it’s easy for you to say, you’re paid to do this”, when you do it in amongst your other work too.

- Generosity: we say “it is more blessed to give than to receive”, and having an independent financial income allows you to live more generously than if you are reliant on receiving other people’s gifts to make your way.

In later chapters he outlines more personal reasons why a bi-vocational approach might suit, or not suit, depending on your particular personality. But these reasons I’ve listed are the competitive advantages he outlines for if someone chooses to do their church work with a bi-vocational approach.

“How do people become like Jesus around here?”

This was one of the reflection questions in the book that stopped and made me think the longest. What does that look like at my church? Do I think the way we operate is effective in helping people live like Jesus?

I particularly appreciated this push towards pastors, as the ones leading the community, leading with the example of their own life:

What is certain is that for your leadership to have credibility, and to form people into Christ, it has to come from lived experience deep in the gut, rather than clever theories of the head. It must echo a genuine encounter with Jesus. If it doesn’t, your people will know, and it just won’t fly. Any competent leader can run a church, organise meetings, and develop strategies, but what is most needed from a pastor is the ongoing experience of knowing and following Jesus, as well as the ability to help others have these transformative encounters.

As a bi-vocational pastor, it will always be tempting to skip the disciplines and practices that form us, and to get on with the various tasks that demand your time. But a pastor who isn’t ministering from a centred life is worse than no pastor at all.

There are countless books that can help you engage in practices that form you and allow you to encounter Jesus, but the bottom line is that it must happen and it has to be real. You cannot rely on your organisational skills, or preaching skills, to get you by. Your energy must come from a life earthed in a relationship with Jesus.

A useful, challenging reminder for me.

Some of the reflection questions at the end of this chapter were also great:

- “How do people become like Jesus around here?” How would you answer that question for your own church?

- The way a ‘centred life’ looks will depend on your current life stage. How does it look for you at present?

- If you aren’t living a life centred on Jesus, then what can you change to put this key element in place?

- Describe the culture of the church you hope for. If this is different from the church culture you currently experience, how can you help the church change directions?

Nuts and bolts of leading a team that’s structured like this

There’s a chapter where he maps out some of the pragmatic realities of trying to lead a church without a single full time pastor. First of these is about how you build a team to cover all the bases. Building a wider team of people who are not full time means you get a wider diversity of skills, experience and gifting. This is a good thing! You will have the things you are exceptionally good at, and also things you’re terrible at. Sharing the load means you can focus on your strengths, and find people whose strengths complement yours.

He leans on the work of Alan Hirsch who uses some archetypal roles from Ephesians 4 to think about different skill sets in a diverse church leadership team:

- Apostle: the pioneer. Seeing new opportunities and having the drive and initiative to make them happen and lead a group towards them.

- Prophet: the truth teller. Questioning the status quo, and calling people back when they’re on a dangerous path.

- Evangelist – the recruiter. Drawing in other people to the mission, often focused outside the church community.

- Shepherd – the nurturer. Caring and protecting people, helping them grow to maturity.

- Teacher – the communicator. Able to teach people things about life and faith in a way that helps them grow.

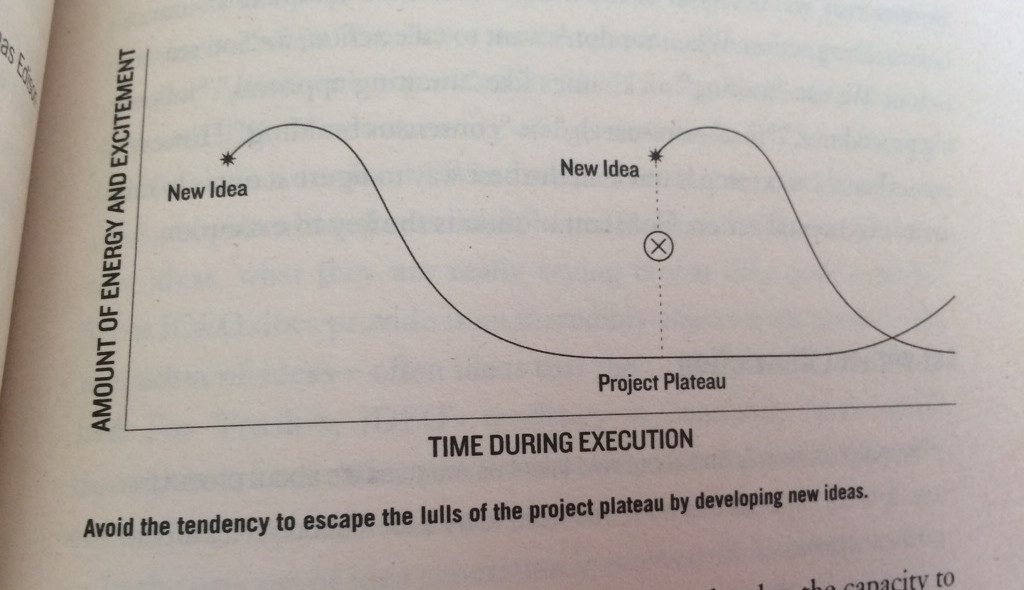

The other part of the nuts and bolts is the prioritisation – you simply can’t get everything done. This is very familiar to me from a software engineering career: there is always more work that could be done. There’s never a true “finish” point.

He suggests one of the tools we use at work too: a simple Urgency/Important matrix, with these kinds of examples:

- Not important, not urgent: organising your desk, archiving emails, useless meetings.

- Not important, but urgent: phone calls, texts, some meetings.

- Not urgent, but important: forward planning, relationship development, values clarification, strategic teaching prep.

- Important, urgent: crisis response, sermon preparation, pressing team or culture problems.

As a part timer, you probably need to accept that the amount you get done will never feel like enough compared to all the things you could do. So you need to focus, and be okay with saying no. You need the things in both “important” quadrants. And you probably need to get used to saying “no” to some things that are urgent, but not that important. Whether you hand it off to someone else, or just accept that it’s okay for it to not get done – that is okay.

Other audiences for the same message

So I found this book really helpful. As someone with a full time career that’s not related to church at all, and as someone who grew up with both parents in full time careers that are about serving the church, having a clear and compelling case made for “why not both” was super helpful.

As I neared the end of the book the degree to which the practical advice in the book was geared towards those who default to full time church work, but are considering bi-vocational, struck me. I’m coming from the other direction, and similarly practical advice would be useful there. If the future really is bi-vocational, we need to not only convince some pastors to take on other jobs, we need to convince a whole lot of people with full time careers to dial back their ambitions there to make some space for a church-serving vocation as well.

The day I bought this book was actually when Hamo came to speak at my church, and I didn’t put together that he was the author of the book mum had mentioned until the end, but I loved his message. It was targeted more at those with existing careers, but from an angle of seeing your work as an opportunity for service and worship, rather than carving out space for explicit work in and for the church.

The sermon is online and well worth a listen. The opening story was so cringe-worthy and I was definitely expecting it to have some corny redeeming plot-twist, and the fact that it didn’t, the story ending without any resolution to the awkwardness, immediately helped me respect where this guy was coming from: no bullshit.

If you’re interested in a 40 minute talk rather than a 200 page book, this is a great place to start:

So, is my future bi-vocational too?

Yep, I think so.